Elliott Hannah, age 14, is happy to play hockey again after fracturing both bones in his forearm. The bones set incorrectly, so Dr. Stephanie Russo, pediatric hand and peripheral nerve surgeon in Akron Children’s orthopedics department, used a 3D printing application to surgically correct the old injury.

What hockey player doesn’t dream of scoring a first period goal? It was a perfect moment for Elliott Hannah, age 14, as he shot and scored.

But elation quickly turned to pain when one of the opposing team’s defensemen checked Elliott while trying to steal the puck. The force of that collision caused Elliott’s right hand and forearm to twist against his chest. Elliott, who has played ice hockey since he was four, knew the injury was bad. He left the ice quickly and drove with his mother to the emergency room.

In the ER, Elliott and his mom, Amy Hannah, learned he had fractured both bones in his forearm, known as the ulna and radius. Elliott was sedated while two orthopedic surgeons reset the bones, placed a temporary splint around his wrist and forearm and sent him home.

Dealing with broken forearm bones

A few days later, Elliott saw an orthopedic surgeon, who took an X-ray and determined both forearm bones were properly aligned. A cast was then placed around Elliott’s forearm to protect it.

Elliott Hannah wears a cast after he fractured both bones in his forearm during a hockey game.

Six weeks later, Elliott returned to the doctor to have the cast removed. The doctor took another X-ray and said everything looked fine.

Elliott didn’t feel fine, however. It hurt to rotate his forearm to turn his palm up (called supination), and his thumb didn’t appear to line up normally. Within 10 days, he returned to the orthopedic doctor, who looked at the imaging again and determined that the bones had set incorrectly.

“We were told that because Elliott is a kid, everything will straighten out as he grows,” Amy said. “The doctor referred Elliott to an occupational therapist for exercises to strengthen his wrist and forearm.”

Lingering pain requires second opinion

The exercises gave Elliott enough movement, so he could function at hockey and dance, another one of his extracurricular activities.

“For the first couple of weeks, anything involving floor dancing was really hard,” said Elliott, who participates in multiple dance genres, including hip hop, jazz, contemporary and musical theatre. “We do push-ups and other conditioning exercises before dancing, and I struggled.”

Part of a competitive dance group, Elliott Hannah participates in multiple dance genres, including hip hop, jazz, contemporary and musical theatre.

At hockey, Elliott also complained of pain, which concerned Elliott’s hockey coach.

“He told us, ‘You need to get a second and third opinion,’” Amy said. “He explained that Elliott is probably almost done growing.”

Amy’s friend suggested Elliott see Stephanie Russo, MD, PhD, pediatric hand and peripheral nerve surgeon in Akron Children’s orthopedics department. Amy also took Elliott to another orthopedics facility closer to their home in Shaker Heights, Ohio. That doctor recommended surgery and told the Hannahs, “Go to Akron Children’s. They specialize in kids.”

Meeting Dr. Stephanie Russo

By the time Elliott met Dr. Russo over four months had passed since he fractured his radius and ulna. He was also seen by a hand therapist in Children’s Pediatric Hand and Upper Extremity Clinic.

Dr. Russo was able to determine the degree to which Elliott’s forearm mobility and function had declined. For example, the normal turning radius of a forearm in supination is 75 to 80 degrees, but in Elliott’s case, his turning radius was only 10 degrees. Another issue was the joint between the two bones in the forearm and how the bones moved around each other, which would be impacted because Elliott’s growth plates were nearly closed.

Before suggesting surgery, Dr. Russo wanted to consult with her colleagues and investigate using new surgical planning technology.

“We liked how thorough Dr. Russo was and that she didn’t push surgery,” Amy said. “No parent wants to put their child through surgery if avoidable.”

Two weeks later, Dr. Russo called with a plan to help Elliott. It involved 3D modeling to simulate the surgery in advance along with 3D printed custom guides that would be sterilized and used intraoperatively during surgery to perform the procedure.

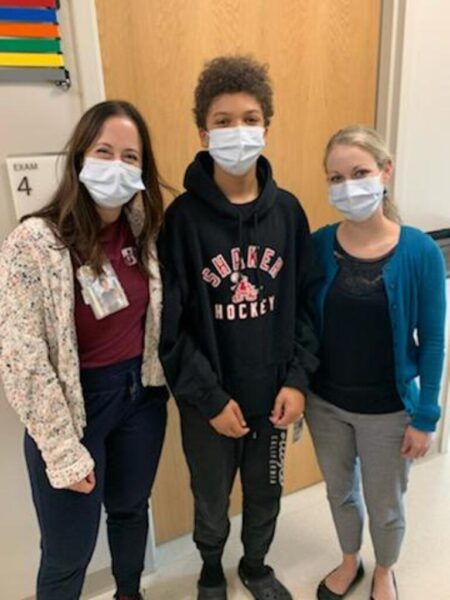

Dr. Stephanie Russo (right) and Jaime Bass, one of the certified hand therapists at Akron Children’s, were important people in ensuring Elliott Hannah rebuilt strength and mobility in his forearm.

3D printing application fixes forearm fractures

Numerous steps were involved to get ready for Elliott’s surgery. The company that Dr. Russo worked with, Materialise, used specialized software. Additionally, CT scans of both of Elliott’s arms were required so the company’s bioengineers could create the custom guides.

“It is the first time this system was used at Akron Children’s,” Dr. Russo said. “The custom 3D guides were designed to accommodate Elliott’s surgical needs, even the hardware used. The benefits are that it can be used with an old injury that has healed and there is substantial deformity that needs to be corrected.”

Regaining ability to turn palm up

After surgery, Elliott met regularly with one of Children’s hand therapists to build strength and mobility in his forearm. Elliott considered his occupational therapy one of the most important steps.

“My advice to anyone going through something similar is to do what you have to do in therapy,” he said. “Remember to do it at home, so you can get full use of your hand back.”

It took 15 weeks post-surgery before Elliott was cleared to play hockey again. The good news is that through Children’s multidisciplinary team approach, he recovered all of his motion, no longer has pain and was able to return to dance and ice hockey.

“Elliott’s surgery was complicated,” said Dr. Russo. “Not every surgery needs 3D modeling, but I wanted to make sure we got everything perfectly right.”