Media exposure of disturbing events and tragedies can have a profound effect on kids. Parents may struggle with how, or even if, they should talk with their children about such events.

Mental health experts at Akron Children’s offer these tips to help parents handle these conversations.

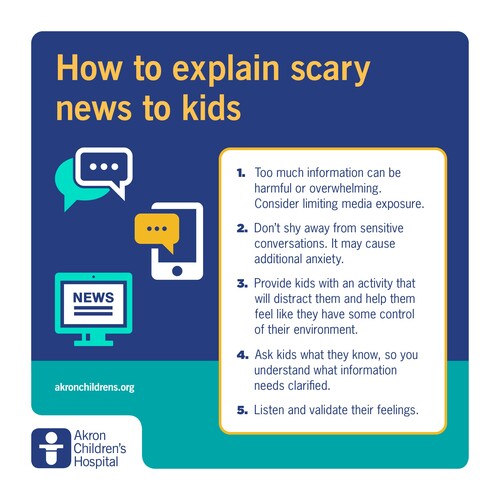

- Before talking to your children, ask what they know to get a sense of their understanding of the events unfolding, as well as their questions and fears.

- Be accurate, correct misinformation, and be reassuring without dwelling on particularly graphic and upsetting details.

- Kids will look to you, observe and likely model your reaction to these events.

- Tune out television and radio for a few days. The repetitive nature of headlines, video and images, especially on television news, can amplify the sense of danger. Point out that things are covered in the news because there are rare, not common events.

- If your child is on social media outlets like Facebook and Twitter, they may be getting too much information – or misinformation – so be prepared to set limits as well. A good rule is to not allow adolescents to have access to their smartphone after bedtime. It’s easy to lose track of time reading Tweets and text messages and a lack of sleep can contribute to a cycle of worry and anxiety.

- How you communicate, of course, depends on the age of your child. Teens may want to talk about the events and voice their opinions. Younger kids might have questions about their safety and need reassurances.

- Keep to a normal routine, if possible. Most kids – and adults too – thrive by following a daily routine with predictable bed times and daily patterns.

- It’s okay to say, “I don’t know,” as in “I don’t know why it happened but many people are working hard to prevent it from happening again.”

- Think of ways for your family to do something tangible, such as to make a donation, or simply go out of your way to counter the bad with “random acts of kindness.”

- It’s okay to acknowledge the truth when children become aware that people have died or are suffering. Don’t offer excessive detail. Instead, focus on efforts by first responders and good Samaritans.

The words of Fred Rogers, of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, are timeless:

“For me, as for all children, the world could have come to seem a scary place to live. But I felt secure with my parents, and they let me know that we were safely together whenever I showed concern about accounts of alarming events in the world. And there was something my mother used to say: ‘Always look for the helpers,’ she’d tell me. ‘There’s always someone who is trying to help.’ I did, and I came to see that the world is full of doctors and nurses, police and firemen, volunteers, neighbors and friends who are ready to jump in to help when things go wrong.”

For additional information, visit the parent resources tab on the Lois and John Orr Family Behavioral Health Center web page. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network also as helpful information.