The first thing you notice about Dr. Robert Parry’s office is that it holds a great number of clues about him. A motorized skateboard is propped against a wall, below a mounted, fiberglass sailfish, fabricated from a prize catch off the coast of Key West. He has a degree in electrical engineering, which like pediatric surgery, appeals to an innate fascination with how things work, how to troubleshoot problems and how to fix them.

He likes the water. A lot. The Essential Knot Book shares shelf space with anatomy books. Windsurfing and boating photos are scattered about. He restored a classic boat made of wood, and he owns a trawler designed for catching shrimp.

Dr. Parry has been on staff at Akron Children’s since 2011. His wife, Jennifer, a nurse practitioner with whom he has 3 grown children, encouraged him to come to Akron Children’s from Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital. He’s one of 10 general surgeons at Akron Children’s.

In March, Dr. Parry and wife Jen went to Hawaii with son Carter, 20, and daughters Hanna, 20, and Devin, 24.

On nice days, you might catch Dr. Parry skateboarding to work from his home about a mile away.

On cold and blustery weekends, you might find him windsurfing on Lake Erie.

Kite surfing during the early 1990s in Baja.

He grew up in Wellesley, Mass., the son of a Marine Corp colonel. His family has seafaring roots, dating back to when his father’s descendants came to America around the time of the Pilgrims.

Before he even graduated college at the dawn of the microchip age, technology companies tried to woo him. But with duel degrees in electrical engineering and biology, Dr. Parry decided that life sciences was his true calling. “By that point emotionally, I really thought I wanted to do this. I wanted to operate,” he said.

He joined the Navy, which put him through medical school at Cornell University, and he did an internship and his residency at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Md.

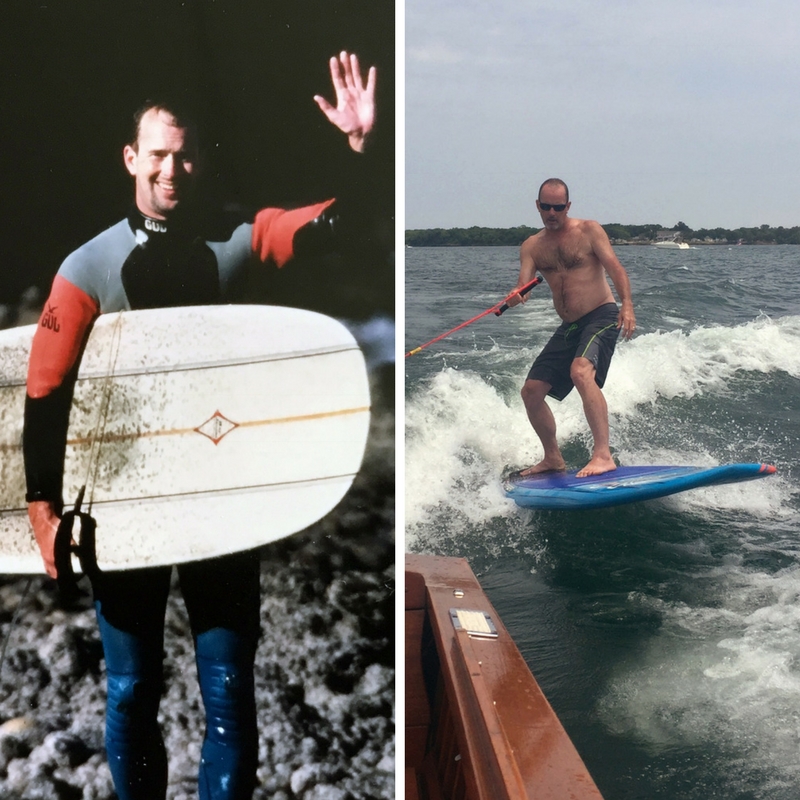

Dr. Parry in the early 1990s during a surf trip in Baja (left), and surfing behind his 21′ Lyman runabout last summer off Kelleys Island.

“I never looked back,” he said. “It was great. It finds you, I guess. I worked harder than I ever worked, and I loved getting up in the morning.”

At age 58, he has performed more than 10,000 surgeries, and his zeal for operating on the smallest humans hasn’t faded. When people are depending on you, it’s easy to get up in the morning, even if it’s at 2 a.m. When a sick child who doesn’t understand what’s happening needs surgery, he asks, “how can you not be excited to go help out?”

“Working with kids for me is fun, I know it sounds weird that operating on kids would be a fun thing, but kids are so resilient, they’re so optimistic. If it’s 90% bad, 10% good, they go right to the 10% good.”

Dr. Parry is known, among other things, for his boxes of colored pens and pencils. After surgery, he draws on fresh dressings a child’s favorite character, everything from Batman to Brownie the Elf (the Cleveland Browns mascot). It’s a way to give his young patients a piece of himself, to let them know, “You’re not just somebody I operated on.”

He has an easy way with children and parents, a low, mellow voice and reassuring demeanor. On a recent afternoon at Cleveland’s MetroHealth Medical Center, where Akron Children’s provides pediatric surgical services, Dr. Parry examined 3 kids, including a brother and sister, with umbilical hernias. It’s a common condition where fat or part of the bowel pokes through an opening in the abdominal muscle. The hole may close by itself or pose no problem, but sometimes it requires surgery.

It’s a relatively simple surgery, but parents, referred here by their pediatricians, are anxious.

Giavanna Joslin, 5, sat on the exam table with her flamingo shoes and pink tights, and Dr. Parry felt around her belly button.

“What did you have for lunch today? I can’t tell,” he teased. The child’s attention was focused on soap bubbles floating in the air, compliments of registered nurse Shay Fitzgerald.

Dr. Parry turned to the parents. “She’s got a little space that’s open, and a little fat that has poked through. Most belly button hernias go away. If it’s still there at 3 or 4, that’s when we fix them.”

Giavanna’s little brother, Rocco, also has one, but it’s small and will likely close on it’s own. With Giavanna, Dr. Parry told parents John and Ashley it’s okay to wait and see.

Each patient gets a custom-made surgical dressing created by Dr. Parry.

“You don’t have to do anything,” he said. “But it can get bigger and it can get annoying. If at any time in life it’s a hassle, then you can do something. There’s nothing you have to feel committed to today.”

A short time later, Dr. Parry examined a 9-month-old boy who was born with an undeveloped anal opening. The condition is called imperforate anus, and it is estimated to occur in about 1 in 5,000 births.

The boy, Luis, was in for a follow-up visit after Dr. Parry had performed surgery that involved pulling the rectum through muscle to the opening.

“He’s looking great,” Dr. Parry told mom Nayatt Lopez, who was concerned about whether Luis was pooping okay. “I’m really happy. I want you to be happy. He’s looking fabulous.”

Dr. Parry has done many of these operations, and he credits a surgeon named Dr. Alberto Pena, who pioneered the procedure at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“Congenital defects keep us in business,” Dr. Parry said. “It’s not glamorous, but it’s unbelievably important. You fix things that are broken and kids grow up without knowing what happened.”

He can talk in expansive detail about fixing things, and also about the other part of his job, the part that engages with kids and their parents. “Three for one” he calls it.

“I can deal with families, I like it,” he said. “It’s not a burden to me. I am empathetic without inhaling it all myself. I can help navigate people through it.

“You have to reload every time and just be a human, be a friend. Let them know you’re going to take care of their child. You’re all in.”